How often are there contradictions between storytelling and historical data?

A friend who read my article Navigating Chaos in the New World Order proposed this question to me back in October. At the time I was distracted with life and wasn’t sure how or even why we should make sense of the conflicting strong opinions permeating the digital sphere related to politics, religion, armed conflict, and other charged topics that pervade our society. Until an article crossed my path “My Beautiful Old House” and other fabrications by Edward Said written in 1999 by Justus Reid Weiner.

Weiner’s article perfectly exemplifies the enigma of the spoken and written word, and casts doubt on the prevalence of objective truths presented by academics, scholars and writers. It called to mind another example of inconsistent accounts of evidence and highlights how we may misperceive authors to be “experts” on a topic simply because they furnished references or have scholarly credentials.

Example 1: The Fabrications of Edward Said

Weiner’s article presents a fascinating account of how Edward Wadie Said, an Egyptian American scholar, peddled in depth lies about his biography and family history in Palestine, related to his family’s origins, property ownership, and the home and town where he grew up. Given Said’s claim to a piece of property that was never owned by his immediate family combined with his pro-Palestine political activism, Weiner remarks how “political ambitions often seem permanently insusceptible of being satisfied through the normal processes of politics”.

The very moment I concluded reading this article, a vocal pro-Palestine / anti-Isreal connection of mine shared one of Said’s books with praise on Instagram. I wondered if he knew Said’s life story had been falsified and I wondered what else Said could have fabricated, exaggerated or omitted in his literary works given the pathological and systemic nature of the lies that were uncovered by Weiner. I wondered if the book by Said contained cherry picked stories to suit a narrative, the same narrative that is partially fueling the conflict in the region today.

It seemed like uncanny timing, presenting the opportunity to analyze the challenge with objectivity faced by authors and scholars in conducting their work and its implications on our perceptions of important issues. It seemed to beg the question: when it comes to storytelling, whom and what should we believe? To answer this, let’s look at another example.

Example 2: Sex at Dawn vs Sex at Dusk

I became curious about the topic of monogamy in humans cira 2012. Wavering over the decision to not marry my boyfriend, and the disdain for the idea of dedicating my life to a marriage and “nuclear family”, I embarked on a mission to answer the questions: are humans meant to be monogamous, is monogamy natural, and what does history and evolutionary biology have to say about the topic. I stumbled across the book Sex at Dawn: the Prehistoric Origins of Modern Sexuality by Christopher Ryan and Cacilda Jetha that presented the case for monogamy not being innate to the sociosexual system of humans.

It was a compelling read about the evolution of human mating that seemed to give support in the form of historical data to the hypothesis that humans were in fact not naturally monogamous and that monogamy arose more as an adaptation to social conditions such as the advent of private property. After reading the book I felt rather pleased that my own lifestyle choices were affirmed…that is until I read Sex At Dusk: Lifting the Shiny Wrapping from Sex at Dawn by Lynn Saxon, published two years after Sex At Dawn.

Using predominantly the same sources, in Sex at Dusk, Saxon analyzed the evidence produced in Sex At Dawn and refuted the book’s conclusions by filling in gaps, making corrections, and revealing how the authors of Sex at Dawn cherry picked studies that supported their thesis and omitted studies and data that contradicted their thesis. It was a thoroughly itemized account of the misrepresented citations and research errors committed by Ryan and Jetha. An example that stood out as particularly shocking was when Saxon showed how in one instance, Ryan and Jetha present an argument by rearranging facts. Ryan and Jetha essentially claim because of A and then B, then came C. When in fact, it was because of C that A and B had occurred.

The Laborious Exercise of Fact Finding

Saxon’s credentials as an evolutionary biologist are immediately apparent in the first chapter of Sex at Dusk. Her knowledge displays a lifetime of dedication to studying and researching the fields of evolutionary biology, primatology, and anthropology. She was not only more of an expert on the topic than Ryan and Jetha, but she also applied critical thinking and the exercise of logic and deductive reasoning to pick apart Ryan and Jetha’s research and in doing so made a much stronger case for monogamy being inherent to the human species.

Saxon proves to be a greater authority and the wealth of data and depth of analysis presented in Sex at Dusk, across a far wider range of research and diverse species, made Ryan and Jetta’s work appear deceitful. It was no wonder then that Sex at Dawn was so highly criticized by academics and scholars and praised mostly by non-academic reviewers in the media. In fact, scholars overwhelmingly reviewed Sex At Dawn negatively and when Ryan originally tried to release the book with Oxford University Press, it was rejected after failing the peer review process.

Likewise, it comes as no surprise that it took Weiner 3 years of fact finding and investigations to uncover the lies and holes in the tale told by Edward Said. Combing through public records and archives in five countries and four continents, Weiner went as far as to inspect property and court records, school records, and conduct countless interviews with tenants of the properties said to be owned by Said’s family, interviews of relatives, neighbors, colleagues, and classmates in the schools Said claims to have attended and so on. I was left wondering:

Is our polarized society due to an inherent aversion to the rigor required to uncover truth?

Aldous Huxley once said “the deepest sin against the human mind is to believe things without evidence”. In 1958 Huxley warned of “the crucial importance of evaluating the use of technology in mass societies susceptible to persuasion”, and this was in an era when we were less deluged with information. The discernment between fact and fiction is perhaps becoming even less obvious in the noise of today’s digital sphere, with great implication to the human species given the global threat of things like violent religious extremism. The discrepancy between individual “realities” continues to be at the root of most human conflict as each conflicting side is able to mobilize support through selective story telling, aka propaganda.

Since Huxley’s Doors of Perception was written in 1954, through to the psychedelic renaissance of today, we’ve become more aware of how the human mind is prone to filtering and selective reasoning. But the daunting challenge of sifting through the accumulation of data or “evidence” in 2023 only demands more dedication to the discovery of truth than ever before. We do however have an abundance of information available to us digitally, which gives today’s fact finders a clear advantage. The expense of time, money and effort seem to be the biggest hurdles to those seeking to uncover truth.

I couldn’t help but notice that Weiner’s article was published in 1999, long before smartphones hijacked our attention spans and before news articles were designed to be click bait for advertising dollars. I sincerely wondered if today’s journalists were capable, willing or incentivized to conduct such lengthy investigations and was left concerned that perhaps the art of investigative journalism has been lost.

I wondered, are reporters today willing to travel to five countries to conduct a fact finding expedition such as the one conducted by Weiner, one that arguably pales in comparison to a supreme court discovery process? Which publications would fund such an expedition? Perhaps none, and we are faced with being mostly subjected to stories riddled with bias, unconfirmed hypothesis, and outright false statements.

So how are we to navigate bias and cherry picked “evidence”?

If we are to define a fact as anything that actually happened, or that which cannot be disputed, then given how often information is disseminated to justify subjective beliefs and agendas, it would help discern fact from fiction by consuming all information through the lens of the harshest skeptic. For those conducting deep dives on a topic they deem important, considering the examples of Said vs Weiner and Ryan/Jetha vs Saxon, it stands to reason that only those who engage in the most laborious endeavor of fact finding bring us closer to truth. And it may be the case that we have become better suited to sitting in the discomfort of not knowing.

The friend that reviewed my article also knows the person who shared Said’s book with praise. This friend recently confessed to feeling paralyzed in not knowing who or what to believe with respect to the Middle East conflict amidst the emotionally charged and polarized narratives. The three of us exemplify how interconnected we all are in the sea of human curiosity fed by the river of endless information exchange. My friend’s paralysis shows how unproductive short sound bites and news stories are to those genuinely seeking to gain a greater understanding of important issues. Perhaps we should heed Albert Einstein’s advice when he said “The only thing that you absolutely have to know is the location of the library.”

And while we can spend more time reading physical books, the new found habit of being spoon fed information by others is probably here to stay, so it’s probably wise to acknowledge that everything we hear and read is filtered through a subjective lens. And in doing so, consider that the ease and likeliness of fact omission (as opposed to outright lies) and also the motives of authors and story tellers.

Even the most respected scholar’s hypotheses can be fueled by bias, like how curiosity is shaped by personal experience, and that bias may be fueled by emotion. And it is perhaps the strongest emotions that prompt people to story tell; these may be primitive ones like anger, rage, victimhood, entitlement and so on, carrying potential to alienate, fuel polarity and divide. As we engage with humans across the world from all political and religious spectrums, considering the obvious and potential less obvious motives of the story teller will be crucial for our evolution as consumers of media.

So to answer the original question of:

How often is there a contradiction between storytelling and historical data?

The answer is, most probably, very often. That is because storytelling presents the inevitable possibility of selective presentation of facts to construct an argument in support of a thesis. One consideration among many possible personal, religious and political motivations, is that a provocative or shocking thesis or title of written work is more likely to maximize income for its producer.

And with the possibility of more sinister intentions behind propaganda, such as justifying war, mass murder and the revocation of human rights, all which may proliferate with global population growth, we may want to appreciate the great power that amassing more fact-based knowledge can bring to those who seek freedom from tyranny and oppression (which I think a decent portion of those reading this do) and how crucial the lost art of cracking open history books might be to our survival.

So what is the value of story telling given its inherent subjectivity?

While combing through vast amounts of data in search of the “truth” may be a useful exercise, especially when tasked with action or an important decision, a recent personal experience exemplifies why we should not discount story telling. As outlined in my previous article, a pattern emerged amongst friends I’ve spoken to about the war.

When I pressed those who had firmly picked a “side”, what eventually emerged in their passionate discourse was a desire to alleviate suffering for those they perceived to be suffering or have suffered “the most”. That perception also seemed highly influenced by friends and family members. There was simply more empathy for whoever they connected with most on their unique life path.

The importance of story telling to both individuals and the collective is highlighted by Henry Melvill, a British Priest and former Canon of St. Paul’s Cathedral, who wrote: “Ye cannot live only for yourselves. A thousand fibres connect you with your fellowmen; and along those fibres, as along sympathetic threads, run your actions as causes, and return to you as effects.”

So in our new world of rapid cross-border information exchange, the opportunity to empathize with a greater amount of fellow humans has exploded and the awareness, understanding and harmony that empathy can foster is beyond question. If we liken our in person and digital exchanges to “sympathetic threads” that connect humanity, then storytelling is most certainly a catalyst for peace.

Where does that leave us in our increasingly digital age?

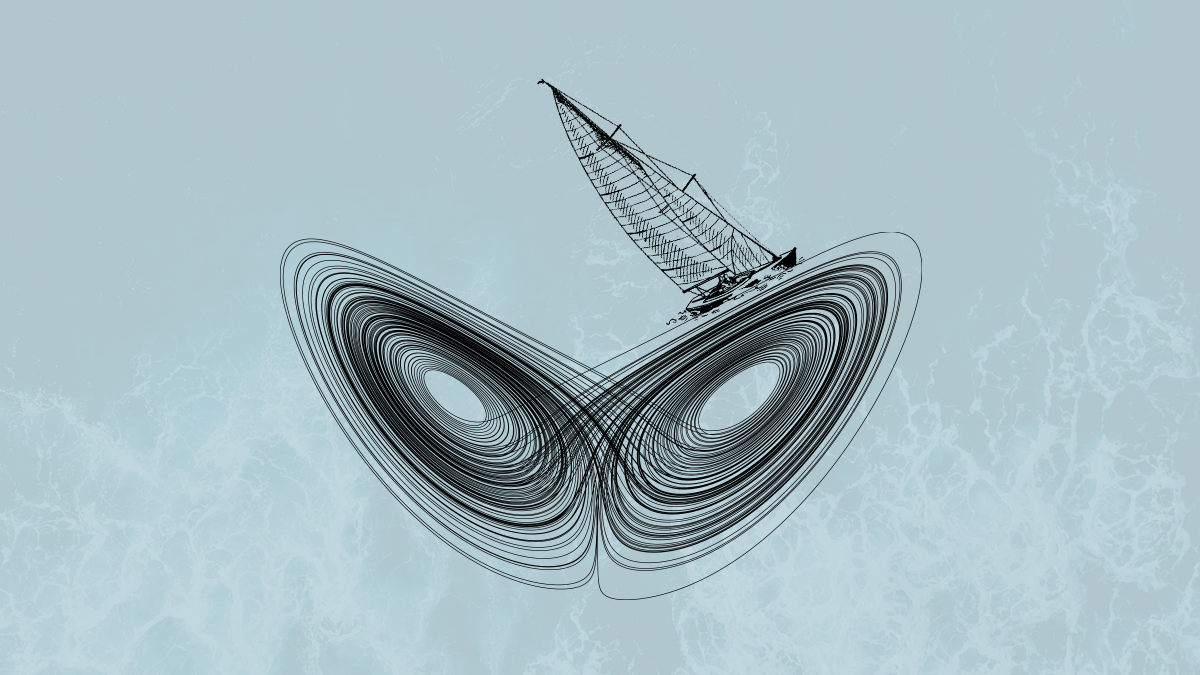

In the labyrinth of our digital age where storytelling and data collide, we will remain in a complex landscape of truth and narrative intertwined. Storytelling, though inherently subjective, is not devoid of value. It is a tapestry woven with threads of human experience, capable of fostering empathy and bridging divide. Though it behooves us to tread carefully and with a skeptic's lens, recognizing the allure and peril of narratives that may obscure facts.

Combining diligent fact-finding with the art of storytelling can serve as our beacon and guide us towards a deeper understanding of our world and each other. This delicate balance between the empirical and the narrative is not just a scholarly pursuit but a collective responsibility, one that demands commitment to discerning the multifaceted truths that shape our shared human experience.

….

As if in each of us

There once was a fire

And for some of us

There seem as if there are only ashes now

But when we dig in the ashes

We find one ember

…..

That's what you and I are here to celebrate

That though we've lived our life totally involved in the world

We know, We know that we're of the spirit

The ember gets stronger

Flame starts to flicker a bit

And pretty soon you realize that all we're going to do for eternity

Is sit around the fire

- Ram Dass